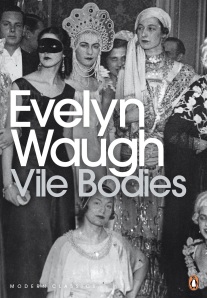

There are moments in Evelyn Waugh’s Vile Bodies when you don’t know whether to laugh or despair. The darkly comic novel does a scathing take on the 1920s London’s culture of hedonistic living and near-anarchic levels of partying. The ‘Bright, Young People’, as they were christened by the media of the period, were mostly men and women from the aristocracy and the upper classes, bohemians and artists. Life for them was one round of parties and balls after another, and if they weren’t having an impromptu picnic at someone’s country house, they were living it up at races or guzzling champagne at art openings. You would laugh at their antics, if you weren’t so afraid for their health and sanity. Waugh’s novel captures perfectly the ‘carpe diem’ attitude of these young people. It strings together the absurd events that dot the life of a young writer Adam Fenwick-Symes in the inter-war years, and characters that populate this period of his life are among the most richly comic to ever appear in literature.

There are moments in Evelyn Waugh’s Vile Bodies when you don’t know whether to laugh or despair. The darkly comic novel does a scathing take on the 1920s London’s culture of hedonistic living and near-anarchic levels of partying. The ‘Bright, Young People’, as they were christened by the media of the period, were mostly men and women from the aristocracy and the upper classes, bohemians and artists. Life for them was one round of parties and balls after another, and if they weren’t having an impromptu picnic at someone’s country house, they were living it up at races or guzzling champagne at art openings. You would laugh at their antics, if you weren’t so afraid for their health and sanity. Waugh’s novel captures perfectly the ‘carpe diem’ attitude of these young people. It strings together the absurd events that dot the life of a young writer Adam Fenwick-Symes in the inter-war years, and characters that populate this period of his life are among the most richly comic to ever appear in literature.

Briefly, the novel follows the travails of Adam, who has just returned to London after two months in Paris, where he finished the manuscript of his memoirs. He’s engaged to the beautiful Nina Blount and the money from his book is expected to support him and his future wife in the style they’re accustomed to. Unfortunately, custom officials are offended by the ‘dirt’ they perceive in the book, and informing Adam that their job is to prevent “works like this coming into the country”, burn the only existing manuscript. After this disaster, it’s an on-again, off-again engagement for Adam and Nina, as the former wins money off a drunken bet, loses it when he hands it to a drunk Major for ‘investment’, gets more money when the horse he has bet on wins a race and loses it all again when the Major disappears with his money. In between, he visits Nina’s eccentric father, Colonel Blount to ask for financial help, begins writing the ‘Mr Chatterbox’ gossip column for a newspaper, has surreal conversation with his landlady Lottie Crump, and has a day at the races where his friend Agatha Runcible gets drunk and drives a race car off the tracks. It’s one bizarre thing after another, the characters are all memorable – even those with little cameos like the car-owning rector and the Prime Minister Mr Outrage – and the pace of the action never flags.

The harum-scarum plot and high-living characters make sense if one looks at the context. The world has just suffered through the most devastating war in history, and it seems like the status quo has been restored in politics. The 1920s were years of sustained economic prosperity (they were, after all, The Roaring Twenties) and saw the rise of such cultural phenomena as Jazz music, Art Deco and the Flapper. All these – the seeming formlessness of Jazz, the modernist and functional lines of Art Deco and the unfettered sexuality and cocktail-swilling of the Flapper – flew in the face of conformity. The Bright Young People were the very embodiment of these unorthodox attitudes, as reflected in their decadent lifestyles. In fact, Waugh himself was a member of this set, along with novelist Nancy Mitford, heir to the Guinness brewing fortune Bryan Moyne and his wife Diana, photographer Cecil Beaton and novelist Anthony Powell. Their all-night parties, hard drinking, elaborate pranks – the’ Bruno Hat Hoax’ art exhibition is practically legend – were only fuelled by widespread tabloid coverage.

Yet, there’s a hard-bitten cynicism and brittleness in Vile Bodies, the kind that knows these people live in the moment, because they know the good times can’t last forever. Like I said at the beginning of this post, often you don’t know whether to laugh or to cry. The Bright Young People seem to lead such hopeless existences. It’s like they’re in shell-shock and the only way they feel alive is when they’re drunk and dancing and creating mayhem. Even their attitude towards love is bewildering. Perhaps Waugh is exaggerating for comic effect, but his depiction of the romantic exchanges between Adam and Nina is very telling. For instance, when Adam informs Nina that he has no money on which to marry her, Nina replies, “Oh Adam, you are a bore”. Nina eventually marries someone else, although this doesn’t stop her and Adam from continuing to sleep with each other. They’re perfectly cool and brazen even when spending Christmas at Nina’s house after they tell her forgetful father that Adam is her husband. Blasé is what their attitude is. Waugh’s tone too changes from light-hearted to bitter by the end of the book, by which time the Second World War has begun. Nowhere is the author’s despair clearer than in this passage:

“Masked parties, Savage parties, Victorian parties, Greek parties, Wild West parties, Russian parties, Circus parties, parties where one had to dress as somebody else, almost naked parties at St. John’s Wood, parties in flats and studios and houses and ships and hotels and nightclubs, in windmills and swimming baths, tea parties at school where one ate muffins and meringues and tinned crab, parties at Oxford where one drank brown sherry and smoked Turkish cigarettes, dull dances in London and comic dances in Scotland and disgusting dances in Paris – all that succession and repetition of massed humanity…Those vile bodies…”

So what starts out as a comedy, ends as a tragedy – a bit like Black Adder, if you’ll forgive the comparison. Just like that wonderful television show, Vile Bodies is a sharp comment on a society and an era, and I highly recommend it to anyone who is looking for more than a few good laughs.

Pingback: Pushing Forth: Reading Challenges for 2015 | Bibliofanatique